(Ames, Iowa/via Iowa Capital Dispatch) – Dairy cattle infected by avian influenza in recent months have surprisingly large amounts of the virus in their milk but little in other bodily fluids, according to tests by the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. That makes it easy to confirm whether a lactating cow is infected but makes testing more difficult for other cattle as federal agriculture officials attempt to learn the extent of bovine infections across the nation.

In nasal secretions, blood, feces and urine, “we can find an occasional positive, but those positives are at levels that are almost undetectable,” said Dr. Drew Magstadt, a cattle disease researcher at the Ames lab. His comments were part of an online ISU Extension and Outreach discussion about the virus on Wednesday.

Magstadt discovered about six weeks ago that highly pathogenic avian influenza was the source of a mystery illness among dairy cattle in Texas. It had never been known to infect cattle in the United States before. Since then, the virus has been detected in herds in eight other states, most recently in Colorado. That spread has been caused by the movement of dairy cows from infected herds to previously unaffected herds.

Genetic testing revealed that wild birds initially infected cattle with the virus, but the USDA has found evidence that it has since spread from cow to cow and from cattle to poultry. At least one infected dairy cow had no symptoms of illness. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced last week that fragments of the virus have been detected in the nation’s commercial milk supply even though milk from sick cows is barred from distribution. On Wednesday, it said testing has confirmed that pasteurization — a process of heating milk to kill pathogens — inactivates the virus.

Tests of milk, cottage cheese and sour cream “did not detect any live, infectious virus,” the FDA said. FDA strongly warned against drinking raw milk. Some states, including Iowa, have sought in recent years to expand the unpasteurized milk’s availability for purchase. Also on Wednesday, the USDA said tests of ground beef in states where the virus has been detected showed no evidence of the virus. Dairy cattle are often slaughtered for their meat when their milk production drops.

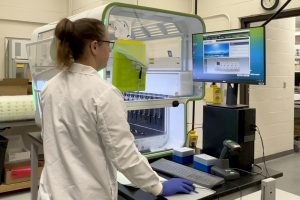

The ISU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory tests samples from animals for viruses such as avian influenza. (Photo courtesy of Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory)

Starting this week, the department requires most lactating dairy cattle to test negative for the virus before they can be transported to different states. Iowa will require labs to report all confirmations of the virus regardless of the animal species, said Dr. Jeff Kaisand, the state veterinarian and a bureau chief for the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship. For now, IDALS will not quarantine dairy farms if their cattle are infected, Kaisand said. Most states have taken a similar approach.

Dr. Yuko Sato, an ISU professor who has researched the virus in poultry, said dairy farmers should take more precautions than what might be required by government officials. She said a bird flu outbreak in 2015 was largely driven by farm-to-farm spread that was the result of insufficient biosecurity measures. About 33 million poultry were culled in Iowa that year. “We waited for the federal government to give us guidance, so we kind of sat on our hands a little bit,” she said. “I encourage the dairy industry to take a proactive stance and try to look at creative solutions, because we’re learning as we speak.”

Highly pathogenic avian influenza is often lethal to poultry — especially chickens — but infected cows usually recover in 10 to 14 days.